This article provides tips for taekwondo instructors.

General Tips[]

The following tips can generally be used for all types of students and instruction.

The Praise Improve Praise: (also called Praise Correct Praise, or Feedback Sandwich) method - when you want to correct a student's technique or form, a common approach is to use "Praise Improve Praise." For example, "That kick was great! Pivot a little more on the bottom foot, and it'll be perfect!" Start with a praise, describe the improvement, and end with a praise. This tends to work well for all types of students, but is especially effective in the long-run with problem students.

The Joplin Plan: When dividing students into groups for group work, the most effective approach has been shown to be to divide students into groups based on their learning level, not their age, athleticism, or other factors. For example, put all the Blue Belts together even if some students are children and some are seniors. The older or more capable students tend to want to help the less capable, and the less capable students will tend to mimic the more capable.

Understand your Student's Goals: Perhaps your original goal as a martial artist was to compete in tournaments, or to learn to defend yourself. Other students might have very different goals however: hobby, sport, weight loss, physical fitness, improvement of a child's self-discipline, martial arts as a family activity, etc. Students comes into the class with different goals. That doesn't mean you have to "sell out" your own teaching philosophy in order to please the students, but it does make sense to keep the students' goals in mind. If your teaching focus is on self defense, but your students are there primarily to lose weight, you might want to accomodate their goals in the development of your lesson plans.

Visualize the Outcome: Many coaches and personal trainers know this trick: if a student is feeling temporarily unmotivated, one way to reengage their enthusiasm is to pause for a moment and get them to visualize the outcome of their efforts. "Let's take a break for a moment. When you get this form right, you'll be ready for your next belt test! Imagine getting ready for class and tying on a new Blue Belt, that's going to feel so good!" Or, "Tired? Let's take a breath. Your kicks are already so much stronger than they were a few months ago. If we keep doing all these kicking drills, by New Years I think you'll have lost another 10 pounds. Imagine what a great way to start the year that will be!" Pausing to actually visualize the long-term goals can help reenergize short-term enthusiasm.

Inch-Stones: "Mile Stones" in a student's progress (such as new belt colors) are big markers of significant progress; the problem is, they're few and far between. Many schools like to more frequently validate the students' feelings that they're constantly making progress. This helps people remain motivated. One approach is called Inch-Stones: find ways to recognize smaller increments of progress. For example, some schools use colored tape to make stripes on belts as awards whenever some new aspect of some technique or form is learned. Different color stripes can be used for different types of accomplishments (e.g., black tape for learning the first half of a form, white tape for mastering a new kick, etc.) Students might get a new stripe as frequently as every week or two; this creates a sense of constant progress that helps keep students engaged.

Don't Over-Tire the Students: By definition, as a martial arts instructor, you are a professional athlete. (You are getting paid to do sport.) Most of your students are not professional athletes; they are probably not is as good a shape as you are. Of course you want to give them a good workout, but martial arts are (unfortunately) an easy way for students to injure themselves if you and they are not careful. Work your students hard, but also recognize that once they get over-tired, that's when they're likely to injure themselves. If you discover that your students in class are now over-tired, switch to low-risk activities, such as forms practice.

Tips for Teaching Young Children[]

Motor Skills - For very young children especially, recognize that their challenge is not entirely related to just discipline and hard work; biologically, young children simply have less-refined neurological systems and gross motor skills. Between ages 7 and 8, an enormous amount of reorganization occurs in the structure of the brain itself (which is why humans have so few memories before that age). That having been said, younger children do have many advantages: they're much less prone to serious injury (biomechanically, the Cube-Square Law is on their side), they have more energy (in short bursts), and they are inherently more limber. What they don't have (yet) is fully-developed gross motor skills.

Boredom - Children get bored much more easily than adults do. It helps to organize classes as short, 10-minute bursts: ten minutes of forms practice, ten minutes of kicking drills, etc. Keep the coursework constantly changing every 10 minutes or so, and you'll keep children's attention better.

Avoid Downtime - If you need a few minutes to set up the next activity, don't allows the children to be idle. Give them something to do, like situps, pushups, stretching, etc. to keep them busy during the few minutes you need.

Save Games for the End - Games can be a fun way to learn, but they're better saved for the end of class, as a reward. Once you start playing games, children have a hard time refocusing on work.

Facing Direction - Avoid having the students face the parents during lessons. Students will tend to look at their parents instead of at the instructor. For example, if the parent-area in your dojang is off to the side, have the students line up facing front.

Avoid Unsupervised Groupings - With adults, you can tell them to get into pairs or small groups and work on something. That works great with adults. With children, not so much. If just one child in the group goes off on a tangent, the other children are likely to follow.

Advocate Fairness - Young children tend to be very preoccupied (overly preoccupied) with fairness and rules. They may "shut down" completely in situations that they percieve to be unfair. So for example, with adult students you might do kicking drills for 10 minutes, and then simply stop a the 10-minute mark, that doesn't always work so well for younger students. Instead, you might try to make sure that every student gets the same number of turns, even if that means going over the drill period by a minute or two. It may be true that "Life isn't fair," but people do appreciate those who try to make life seem more fair, and this is true in spades for very young children.

Leverage their Imaginations - Young children have vivid imaginations and of course they love to play. You can sometimes use that to get extra effort out of them. For example, during the warmup exercises focus on animal exercises (crab walks, bear walks, kangaroo hops, etc.) but really get them to behave like the animal in question as they exercise. Or for example when doing kicking drills, tell them to kick the target as if pretending its a monster or alien. It may seem like a small thing to you, but they often take it seriously and it can make the workout more fun for them.

Child Physiology[]

One important thing to consider when teaching children is that children are not like miniature adults. This is especially important when teaching breaking and sparring. Some things to consider:

Bones: The bony skeleton of an adult is completely connected - the entire skeleton of an adult is bone. For children, this is not true. Much of their skeleton consists of a tough cartilage. As children age, their tough cartilage ossifies to become bone. This ossification occurs into early puberty.

The upshot: if the tough cartilage in a child becomes misshapen due to a sparring or breaking injury, then the resulting ossified bone will also be misshapen when the child grows into a adult. Because the cartilage is softer than bone, it's also more prone to injury from hard impacts. The cartilage heals very rapidly though, as compared to bone. So there may be a tempation to believe that children can "take it" when they receive hard blows, but the truth is the resulting damage doesn't really occur until years later when the misshapen cartilage ossifies. Bottom line: consider carefully before having children do power-breaking or head-contact sparring (in general, both things should probably be avoided for children). Also: avoid heavy weight-training until adolescence (though body-weight training is okay).

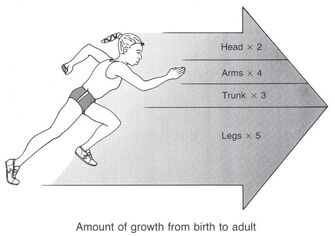

Children are not miniature adults: they are proportioned very differently, and have substantially different skeletal structure and physiology. Image credit: coachr.org

Body Proportions: Everybody knows that babies have large heads, because it's easy to see that they do. What some people might not realize is that even older children have proportionally larger heads than adults...and proportionally shorter legs...as well. A child's head doubles in size from infancy to adulthood, but a child's legs lengthen by a factor of 5.

Upshot: Again head-kicks should be avoided in sparring. A relatively large head is supported by a comparatively thin neck, meaning that even if no cranial injuries occur, injuries to the vertebrae in the neck may. Also recognize that (being a kicking martial art) the fact that a child's legs are relatively short compared to their bodies puts some constraints on the types of maneuvers they're able to perform well. The good news is, it means a child's kicking abilities will develop quickly as they age.

Gross Motor Skills: The ability to finely coordinate large-muscle groups is called gross motor skills. The ability to finely coordinate small-muscle groups (such as fingers and toes) is called fine motor skills. Sports are a great way to accelerate the development of gross motor skills. That having been said, a child's coordination is going to be constrained to some extent by their neurology: they literally do not have the full neurological structure yet that provides the same level of gross motor skill as an adult.

Upshot: Children will generally not have as much kicking precision when they are young as they will when they get older. In board-breaking, for example, children may tend to kick a board off-center more than an adult would. This isn't always due to a lack of focus, the child literally may not have a sufficiently developed neurological structure yet to achieve that level of fine control over large leg muscles. That doesn't mean they shouldn't continue to try, but one should remain aware that the child is constrained to some extent by his or her own physiology. The same goes for sparring: there will be more kicks that are off-target, despite a child's best efforts.

Lungs: Children's breathing is less fully developed than adults'. The average six year old child must inhale 38 liters of air to get 1 liter of oxygen. The average 18 year old needs to inhale only 28 liters of air to get 1 liter of oxygen.

Upshot: Children tire more easily than adults, but are less aware of how tired they are. Of course the goal of working out is to push ourselves just up to the edge of our limits, but one should be aware that those limits can come up relatively quickly and unexpectedly in children.

Additional Information: http://www.coachr.org/growth_and_development.htm

Tips for Teaching Special Needs Students[]

Communication - Special Needs students are often more easily confused as compared to other students of the same age. This means you not only must repeat instructions more, but find different ways of conveying the same information. For example, explain the instruction, demonstrate the instruction, diagram the instruction, use a doll or action-figure to explain the instruction, etc. Remember the old adage: "If you want to be understood, communicate 7 times in 7 ways."

Information Processing - While it's true for everybody that "different people learn differently" (visual learners, auditory learners, kinetic learners, etc.) this can be especially true for Special Needs students. Some Special Needs students can learn only in one way. Some may need to learn the names of the techniques, and then recite the names as they perform them. For others, language may be a distraction rather than an aid. You may need to adapt the way you teach to the needs of the student, to a greater extent than you normally already do.

Frustration - Special Needs students tend to be more easily frustrated, and to stay frustrated longer. When that happens, switch to doing something you know they can do well. For example, practice something they've already mastered. Frustration isn't just an mental state, it's a biological state, meaning it triggers all kinds of hormonal activity. The implication is that you can't simply use "reason" to make frustration go away; you also have to give the chemicals in the bloodstream time to disipate. So switch to a non-frustrating activity, let the hormonal levels disipate, and then try again.

Self-Esteem - Special Needs students may have lower self-esteem. The Praise Improve Praise technique is especially important with Special Needs students. Also, reinforce that what the student is going through is normal. Everybody feels the way they do, especially at this stage of their training.

Distraction - Special Needs students tend to be more easily distracted. Avoid letting students have down-time during class, keep everybody busy all the time, even if they means they do personal stretching or exercises while you prepare for the next activity.

Focus - Special Needs students often find it difficult to stay on-task for long periods of time. Switch-it-up more frequently in class: stretching, calisthenics, forms practice, kicking drills, etc. It's okay to cycle back to a previous activity. So in a regular class you might do 10 minutes of kicking drills, followed by 10 minutes for forms practice, in a class with many Special Needs students you might do 5 minuts of kicking drills, followed by 5 minutes of forms practice, then back to the kicking drills, then back to the forms, etc. An added benefit is that this makes the repetition phase seem more familiar, and Special Needs students tend to appreciate the familiar.

Mental Stamina - Even with frequent switch-ups, Special Needs students may have difficulty staying focused in a full hour-long class. Consider allowing Special Needs students to complete shorter workouts, perhaps half an hour rather than a full hour.

Routine - Many Special Needs students tend to like routine. "We always start with warmups, then stance drills, then forms practice, then kicking drills" etc. They can get frustrated if the routine is broken. When making lesson plans where you feel it's important to go off-routine at some point, try to save that for the end of the class.

Discipline - Some Special Needs students have difficulty controlling their emotions or controlling themselves verbally. They may have a propensity to fidget or be overly vocal. One fairly common technique for dealing with this is to allow the student to be "in charge" of something (welcoming other students, leading a small group, helping to set up targets, helping with cleanup, etc.).

Additional References:

- http://www.moosin.com/2014/06/why-martial-arts-are-best-for-special-needs

- http://www.kidokwan.org/articles/teaching-special-needs-taekwon-domartial-arts

- http://www.yomchi.org/sites/default/files/thesis/KCohnIV.pdf

Tips for Teaching Teens[]

Competition - Whereas young children tend to feel more easily discouraged by short-term defeat, teenagers have usually learned to enjoy competition, especially team competitions. Try to organize class competitions based on size, strength, and ability rather than age. Encourage participation in competitive activities: tournaments, demo teams, etc.

Taekwondo as a Social Activity - Probably moreso than most students, taekwondo class may be used by teenagers to make new friends. Younger children tend to be more opportunistic in terms of friend-making; older students tend to have more avenues for friend-making - but teenagers are constantly looking for ways to extend their social circles. This can complicate the classroom dynamics (especially when classmates start to date, which invariably will happen at some point) but it also creates a terrific opportunity to create a strong core team of taekwondo enthusiasts. If you work with the school's owner/manager to find ways to make before-class and after-class activities more welcoming without being disrupting to ongoing classes, you may discover teenagers showing up well before class starts and hanging-out well after class ends. For example, put teenager volunteers to work cleaning equipment, folding flyers, making banners, or improving the dojang - to you it's work, to them it's an opportunity to socialize.

Teenage Marketing - Enthusiastic teenagers may be your school's best marketers. Facebook, Twitter, word-of-mouth, etc. - moreso than other students, teenagers are likely to bring new students to your school.

Games - Teenagers tend to like a "goofier / sillier" style of play, for example "Taekwondo Dance Contests" or "Movie Fight-Scene Choreography." Make sure these things are done as teams / groups, since teenage years are also the years when students may be most mortified by personal embarrassment!

Change of Scenery - This isn't always practical, but moreso than many students, teenagers tend to enjoy a change of scenery. For example, if there's a park very near to your school (and with the parents' permission of course), taking the class to the park for an outdoor workout on a nice day is a great way to create new energy in the class. If there's another martial arts school just around the corner (even if it's a different style), perhaps consider a joint workout session one day, visiting each other's schools.

Karate on Fire!

"Candle drills" are a fun and cinematic way to improve snap

Cool Stuff - Moreso than most students, teenagers tend to enjoy the "Hollywood" aspects of martial arts. Games and actvities that have the "coolness" factor might not be safe to perform with younger children, but okay for teenagers. For example, punching at candle flames (to blow them out) can be a fun way to improve speed and snap.

Bling - Moreso than most students, teenagers tend to enjoy bling, taekwondo tee-shirts, iPhone cases, backpacks, jewelry, etc. If nothing else, acknowledge the enthusiasm when you see it, or even take advantage of it by using inexpensive bling as classroom rewards.

Tips for Teaching Seniors[]

You're never too old to start learning taekwondo, but taekwondo can be hard on older students. Taekwondo involves high, jumping, spinning, acrobatic kicks. Jumping and spinning are two things seniors are most likely to injure themselves doing. Generally speaking, older students will not have too much trouble with Forms practice or with simple kicking techniques (Roundhouse, Front Kick, Side Kick, etc.). Even Breaking should not be a problem if the strikes and kicks are simple (as opposed to jump/spin). Seniors are much more likely to injure themselves during activities such as jump side kicks (especially when jumping over obstacles), tornado kicks, etc. Some things to keep in mind:

- Strength - Even if a person exercises the same amount every day over their entire life, they still lose as much as 25% of their muscle mass as they age. Older humans are inherently just not as strong as younger humans. Example: imagine yourself doing a one-legged jump while carrying 1/4th of your body weight (say 40 pounds of weights); that's what a 25% muscle-mass reduction translates into. How many one-legged jumps can you do while carrying a 40-pound weight?

- Reflexes - Older students will have slower reflexes. This generally isn't going to affect their ability to perform Forms or do Breaking, but it will affect their ability to spar.

- Prior Injuries - Older students often have a lifetime of prior injuries to contend with. Even before they started taking your taekwondo class, they've already had a history of myriad injuries: sprains and broken bones that continue to bother them to this day. Hips, knees, and ankles are especially vulnerable.

- Range of motion - Older students generally do not enjoy a full range of movement: their neck, spine, shoulders, etc. simply do not rotate through the full range of motion that younger students enjoy. Looking well over the shoulder as they lead into a spin-kick simply may not be possible for an older student. Even without prior injuries, age-related arthritis is going to make older joints more vulnerable.

- Healing - Seniors heal much more slowly. An injury that might take a week to heal completely in a teenage student can easily take a month or more to heal in an older student.

- Stretching - Older students will require more stretching, more warmup before stretching, and will benefit most from cool-down stretching at the end of the workout.

- Vision/Hearing - Older students generally will not hear or see as well. Even older students who do not need glasses are unable to focus their eyes as quickly or through as large a range of distances as younger students. (Just as the skin loses its elasticity as you age, so does the surface of your eyes, meaning that your ability to focus your eyes near or far is reduced.) Putting older students at the rear of the class may make it difficult for them to follow the instruction.

- Balance - As you age, the fluid in your inner-ear that provides a sense-of-balance gets thicker. As a child, you can spin around many times before you become dizzy, because that fluid is still very thin. For older students, spinning even once will likely make them quite dizzy. Additional practice at spinning won't make this any better - when you're older, you simply can't spin without becoming dizzy.

What are the implications for teaching taekwondo?

- Emphasize basic kicks - Taekwondo is characterized by jumping and spinning kicks, but for senior students, you're probably going to want to avoid those.

- Stick to kicks that don't require spinning or jumping: front kick, roundhouse, side kick, axe kick, etc.

- Unless you have a particularly athletic senior, probably avoid the tornadoe kick, back kick, back hook kick, etc.

- Some of your stronger seniors might be able to manage skip kicks, such as the skip roundhouse, but you might want to avoid even those. Why? Because injuries take so long to heal, even a light-sprain can keep your senior out of training for a long time. Senior students are there for the exercise and for fitness, so don't risk injuries, despite the temptation.

- Emphasize blocks, strikes and punches - While seniors do have problems with many kicks, they generally won't have much difficulty with hand techniques, and there's little risk of injury, so this is a great area to emphasize.

- Light impact is better than no impact - Contrary some popular misconceptions, light impact is actually good for joints and bones; it strengthens them. So don't try to make your class "impact free" - let your seniors hit and kick targets and shields. Keep the targets low for the kicks of course, and encourge light contact.

- Emphasize forms - For seniors, doing forms (poomsae, teul) is a great cardio workout, just like tai chi. Forms practice also strengthens legs and strengthens core muscles. Learning and memorizing new forms is also a good mental workout. Don't be afraid to teach seniors new forms frequently.

- Avoid injury - Don't take chances with injury. It's better to have active seniors working out frequently than to have a senior who must take a long break due to a minor injury. So if you see a senior students who appears to be "doing great", avoid the temptation to push their abilities too far.

- Stretching and calisthenics - For a class full of seniors, you'll want to devote more time to stretching, but you will probably need less time for calisthenics. Forms practice and kicking drills are themselves hard exercise for seniors, so you won't need as much calisthenics for the warmup. Avoid problematic stretches, such as standing toe-touches and hurdler's stretches. (See Taekwondo Stretching for more details.)

- Modified free sparring - While seniors may not be up to actual free sparring, a class of seniors can still enjoy games such as shoulder sparring (in sparring stances, the competitors move and turn in an attempt to tap each other on the shoulder).

- Keep it taekwondo - Try to not turn a seniors taekwondo class into a general fitness class. Seniors can still practice forms, they can still do kicking drills, punching/striking drills, and blocking drills. You can still be true to the spirit of taekwondo in a class full of seniors.

Tips for Teaching Self Defense[]

Street Clothes - Designate some class sessions as Street Clothes classes. Have the students wear normal clothing to practice real-world self-defense techniques. Ideally the students should wear street shoes as well, in which case you'll probably want to practice someplace other than the dojang floor.

See also: Taekwondo Self Defense.

See Also[]

References[]

- Sang H. Kim's book on Teaching Martial Arts on Amazon.com

- Sang H. Kim's book Martial Arts Instructor's Desk Reference includes useful information for taekwondo instructors, owners and managers of taekwondo schools, and organizers of taekwondo tournaments.

- http://www.taekwondo-training.com/instructors/tips-and-advice-for-instructors